Metrics Every Team Needs

When you begin implementing observability beyond basic logging, you’ll be presented with a large number of tools that promise the ability to give insight into every aspect of your application. But when we consider observing every possible running line of code and service worker stats, we quickly find ourselves going from almost no information to information overload. Rather than trying to observe everything, it’s better to start with a minimum viable product, and this article will help define the metrics that every team needs to get tracking of their system’s performance.

Along with describing these key metrics, we’ll also discuss the design questions you should ask early on when defining these metrics. The goal is to create metrics that are useful in two ways:

- These metrics should offer an immediate picture of how your system is performing

- These metrics should be stable enough that you can do historical comparisons and see a change in performance

The four key metrics for monitoring your application are all connected to each other, and without any of them you will miss the cause of some failures.

Throughput

Throughput is an APM (Application Performance Monitoring) metric that measures how much work a system can handle in a given time. It counts the number of requests, transactions, or tasks completed successfully. For example, in a web app, it could track how many user requests the server processes per second. Higher throughput means the system is handling more work efficiently. Probably the easiest metric to measure, it gives a quick view of how much capacity is in use.

This author started out in the tech sector doing phone tech support, and one evening I had a report that our core service was totally unavailable. When checking the main site it loaded for me, but when I used a network location outside our office, sure enough the site didn’t load. When working with the on-call engineer, they checked the server’s available memory and response time, and everything looked great. The response was obvious once we thought for a moment: the system was performing extremely well for the handful of users who could get access, everyone else was being blocked by network issues.

It’s a story I have often recounted, but I tell it here again because it highlights an important point: without the rate of traffic for your service, all other performance metrics are meaningless.

Best practices for measuring throughput

While there’s generally little disagreement about the definition of throughput, care should be taken that services that handle requests asynchronously, or those that subdivide a user’s request, don’t count multiple ‘requests’ for a single user request. Special throughput numbers can be created for services like data stores, and these may have higher throughput numbers than the total number of user requests, however in general we should equate throughput with ‘the number of user requests.’

Response time

Response time measures how fast a system or application responds to a user’s request. It tracks the total time from when a user clicks a button, searches, or loads a page until they see the result. Faster response times mean a smoother experience. Slow response times can frustrate users and hurt performance. Keeping response times low is key for a good user experience. Monitoring response times over time can help show whether the product team as a whole is effectively adding features while maintaining performance.

For browser based applications, a long response time may motivate users to go elsewhere; in IoT devices, long response times may make users think their appliance is broken!

Best practices for measuring response times

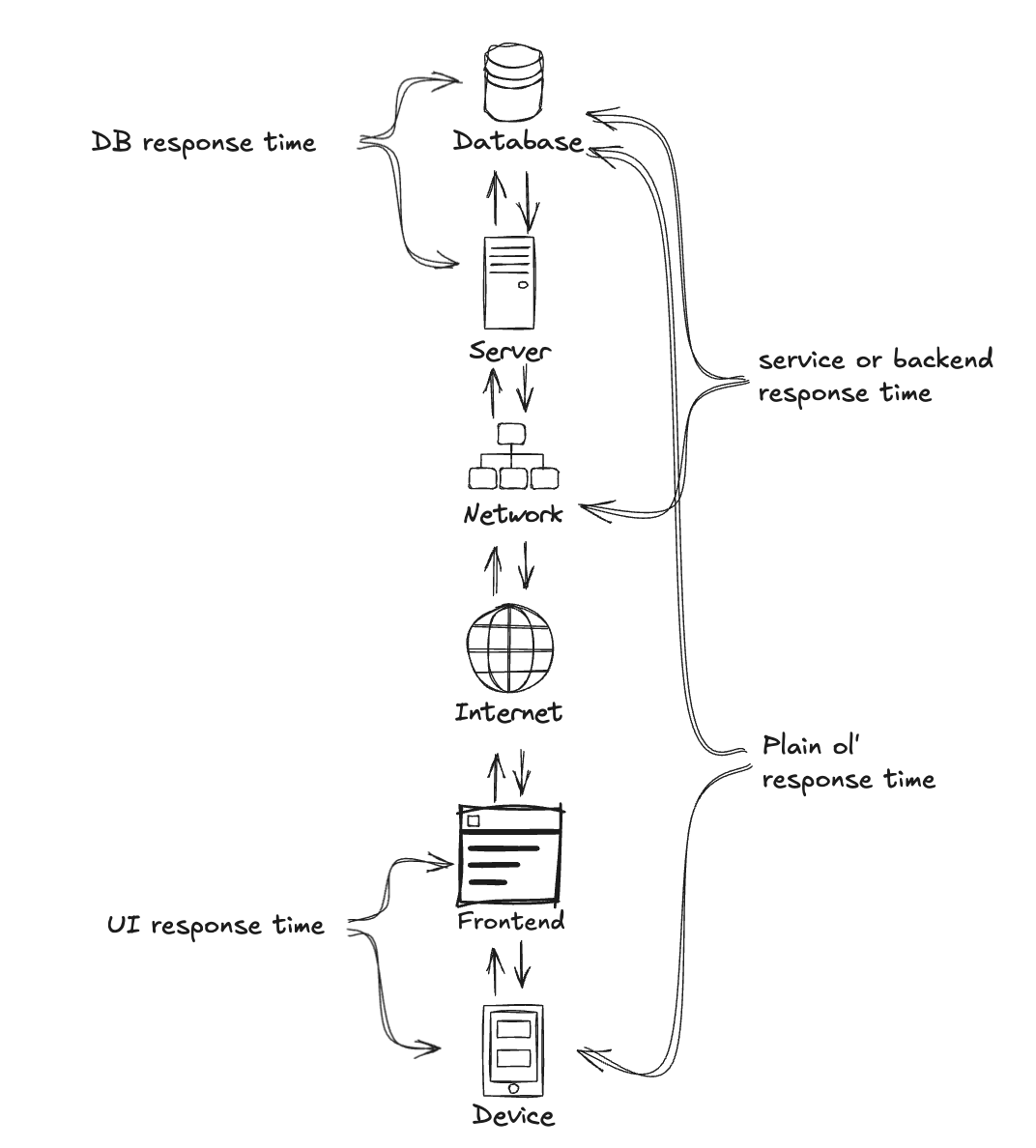

Unlike throughput, response time is a metric with multiple possible interpretations. If a user is running our UI on an extremely old and slow device, and despite returning image data after 4.2 seconds, it takes 12 seconds for the image to render, what was the response time? The question of ‘does network time, frontend rendering time, etc count as part of our response time’ doesn’t have a right answer, it’s just a question of deciding in advance what you’re measuring and sticking with it.

The layers involved in a response can cause some language confusion.

For some services there won’t be much confusion. For example an API service should just be measured on how long it takes to reply to a query. Of course, even with an API, dependencies like databases and message queues will have their own response times, which should be clearly labelled.

In general, the best practice is to clearly label any response time that isn’t covering end-to-end response time, namely ‘how long it takes from a user clicking a button to when they see the result they’re expecting,’ as being a special case versus the standard expectation for response time.

Of the metrics in this article, response time can be the most difficult to measure accurately. While you can see request and response times within your own cloud, it’s quite difficult to see whatg users are actually experiencing with their own broswers and network connections. To measure response times, rather than trying to observe every chunk of time spent in your backend service, consider Checkly to actively monitor your service and record how long each request really takes for common user pathways.

Finally, when viewing response times it’s critical not to just use simple averages to capture performance. Special statistical slices like ‘percent of responses over threshold’ (how often did a user get an unacceptably slow response) and ‘95th percentile response times’ (including all but the very slowest responses, which are often outliers caused by special requests that are predictably quite slow) is critical to get an accurate picture of performance over time.

Infrastructure Metrics

You should always be able to see a small group of metrics that shows the health of your infrastructure. This article doesn’t give a single answer for these infrastructure metrics due to evolution of how we host applications, and what things stress us out now. In the old days of bare metal servers, infrastructure health was usually covered by looking at available memory and CPU usage. But if a team using mainly serverless computation on a public cloud, those numbers would be both meaningless and ephemeral, and of bigger concern is a metric showing how much is being spent to handle all customer requests. Some possible examples of key infrastructure metrics:

- Infrastructure usage/estimated spend - running on a smoothly scaling public cloud, we’re probably not concerned that AWS will run out of RAM, but rather we care if changes to our application have caused us to spend twice as much to handle the same number of user requests.

- Container health - on a managed cluster, questions like ‘how many containers are stuck in a crash loop?’ or ‘what percentage of time are all services available?’ probably encapsulate most of what we care about.

- Unused infrastructure - if, rather than a serverless or other auto-scaling environment, our cloud usage is pre-negotiated and remains stable even during low traffic, it may be that our biggest concern is when we’re paying to run capacity that isn’t actually being used.

These metrics are still critical for any operations or on-call team, and are especially critical when things don’t add up, for example when throughput is way down, but response times are also increasing.

Best practices for monitoring infrastructure

The best practices for infrastructure management could fill a whole book, but at the very highest level the most critical skill for monitoring infrastructure is to perform deep, blameless postmortems any time you have an outage that was user-reported. Outages reported by users are failures that your current observability tools can’t detect. By asking ‘what did we miss’ you’ll begin to identify what needs to be measured better, and surfaced better for your engineers, from your infrastructure.

Error Rate

Error rate is a critical APM metric that quantifies the frequency of failed requests or transactions within an application, expressed as a percentage of total requests. It captures HTTP errors (e.g., 4xx client errors, 5xx server errors), timeouts, exceptions, and can cover business logic failures (e.g., payment declines, API call failures). This metric is often segmented by endpoint, service, or dependency to pinpoint failure hotspots. A high or rising error rate may indicate code defects, infrastructure instability (e.g., database overload), or third-party service degradation. Engineering teams use error rate alongside logs and distributed tracing to diagnose root causes. In SLOs (Service Level Objectives), error rate thresholds (e.g., <0.1%) help enforce reliability targets. Proactive monitoring and alerting on error rate spikes enable faster incident response, reducing MTTR (Mean Time to Repair) and minimizing user impact.

One of the things that makes a metric a key metric is that without observing it, you can have your application fail silently. For example if our frontend is rendering our site beautifully, but the site content is an error message, the response time may look fine, throughput may be fine (or even up since users are hitting reload repeatedly) and our infrastructure metrics may not show a problem. But clearly, this error message should be spiking our application’s error rate.

Best practices for measuring error rate

Error rate will have by far the most disagreement in your team about what counts as an error. In the section above we included things like declined card payments as errors, though that may bristle for some developers, since presumably all our code and our UI can handle a declined card payment just fine, and prompt the user to try a different card. There is no single best answer for what counts as an error, but you should answer the following questions before you start measuring an error rate:

- Do errors raised by code that are not observed by users count as errors?

- Can a single request result in more than one error?

- Do business logic failures count as errors (for example incorrect passwords or API keys, payment declines, or error responses from third party services)?

However you answer these questions, one other best practice is to always count errors that surface to the user, even if no error code is raised. One rather old example is when the team implementes nicesly rendered pages to the ll the user that they’ve encountered an invalid URL or that their request returned a database error. These incidents should all be counted as errors, since the more users see these messages, the more they’ll percieve that something is wrong with this application. For example the following API response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Server: nginx/1.18.0

Date: Wed, 03 Apr 2024 12:00:00 GMT

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 64

Connection: keep-alive

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

{

"body": "Error code 500 an internal server error has occured"

}

This kind of response, with a 200 OK status and an error in the body, may not be great API design, but it should still be registered in your system as an error.

Conclusions: the sturdy table of your application

For all of these four key metrics, I can think of examples where only one of them will be ‘off’ during a certain type of failure. Therefore all four are the table stakes to monitoring a production application.

Conclusions: The Sturdy Table of Your Application

Effective observability begins with tracking four foundational metrics: Throughput, Response Time, Infrastructure Health, and Error Rate. Each of these metrics provides a unique lens into system performance, and missing any one of them can leave critical blind spots in your monitoring strategy.

- Throughput tells you how much your system is handling.

- Response Time reveals how fast it’s serving users.

- Infrastructure Metrics ensure the underlying systems are healthy and cost-efficient.

- Error Rate exposes how often things are failing—even when failures are silent.

Key Takeaways

- No Single Metric Tells the Whole Story

- Define Metrics Clearly and Consistently

- Avoid ambiguity in what constitutes a “response time” or an “error.”

- Document whether metrics include network latency, frontend rendering, or just backend processing.

- Use Percentiles, Not Just Averages

- Track P95/P99 response times to catch latency outliers.

- Monitor error rate trends (not just spikes) to detect gradual degradations.

- Adapt Infrastructure Metrics to Your Stack

- Serverless? Focus on cost efficiency and cold starts.

- Kubernetes? Track container restarts and pod availability.

- Bare metal? Watch CPU, memory, and disk I/O.

- Error Rate Should Reflect User Experience

- Even “soft” errors (like payment declines) should be tracked if they impact UX.

- Beware of false-success responses (HTTP 200s with error messages).

Final Thought: Start Small, Then Expand

While advanced observability (heatmaps, business intelligence, etc.) is valuable, these four metrics form the minimum viable dashboard every team should monitor. Once they’re stable, you can layer on deeper insights—but without them, you’re flying blind.

By measuring these fundamentals, your team can:

✔ Detect anomalies faster

✔ Diagnose root causes more accurately

✔ Prevent minor issues from becoming major outages

Part of starting small is considering the most basic questions first: with Checkly, you can create an automated service to simulate common user requests, and report immedaitely if anything looks incorrect. Checkly’s synthetic monitoring ensures that you’re not relying on users to report problems.

Next Steps:

- Set up dashboards for these four metrics.

- Define your alert thresholds.

- Define your playbooks for incident response.

- Add Checkly to find out about outages before your users do