Context Propagation in OpenTelemetry

Why does OpenTelemetry exist? It grew out of the OpenTracing project, which itself was a response to a basic problem of modern architectures: while microservices had greatly improved operational efficiencey and developer velocity, microservice architectures had proved a disaster for observability. Imagine an architecture like Uber’s:

A diagram of Uber’s thousands of Microservices

Imagine the impossibility of diagnosing problems found during end-to-end testing, if the only tracing or observability we have is isolated to a single service’s context. And so the OpenTelemetry project was founded, fundamentally, to provide insights that go across multiple services within a single cloud.

In pursuit of this lofty goal, one of the most basic features of almost any OpenTelemetry tool, is support for context propagation, a fundamental component that sends information from one service to another and allows traces to cover multiple services.

What is Context?

In OpenTelemetry, context is the information that flows through your system with each request. It carries important details like:

- Trace IDs (to connect all operations in a request)

- Baggage (custom key-value pairs you want to pass along)

- Other metadata needed for observability

Context standards are not defined by the OpenTelemetry project but rather are baced on the W3C Trace Context standards.

Why Context Matters

As mentioned above, modern architectures are complicated. Many outages and other incidents end with engineers examining the logs from a single service, but to get real insight into how requests are processed by your system as a whole, you need context.

Without context:

- Logs, traces, and metrics can’t be connected

- You lose visibility in distributed systems

- Debugging becomes much harder

How Propagation Works

- Injection: When a request starts, the context (trace ID, etc.) gets added to headers

- Extraction: When another service receives the request, it pulls the context from headers

- Passing Along: The context continues flowing through all services in the request

Note that while most OpenTelemetry SDKs and tools propagate context automatically, there’s also the propagation API if you need to manually propagate context. For example, if you are able to see that two time spans should be part of one trace via an unsual method like examining the messages body with a regex, you’d want to work with the propagation API.

The Standards Behind It

OpenTelemetry uses the W3C Trace Context standard (traceparent header) for compatibility. This means:

- Works across different languages and frameworks

- Supported by many observability tools

- Ensures consistent behavior everywhere

Key Components

- Context API: Stores and manages the current context

- Propagators: Handle injecting/extracting context (usually from HTTP headers)

- Baggage: Lets you add custom data that travels with the trace

Baggage is worth a pointer since it’s important to know that you can add operational information beyond observability data, and thereby piggyback off the great work done for context propagation within the OTel project. This might be used to do something like marking test requests sent by synthetic monitoring, so that your datastore knows to route these requests to a test DB.

In Practice

When Service A calls Service B:

- Service A adds trace context to the request headers

- Service B reads those headers to continue the trace

- All spans from both services connect automatically

Why This is Powerful

- No manual correlation needed

- Works across any protocol (HTTP, gRPC, queues, etc.)

- Enables complete observability of distributed transactions

Context propagation turns separate operations into connected stories - making complex systems much easier to understand and troubleshoot.

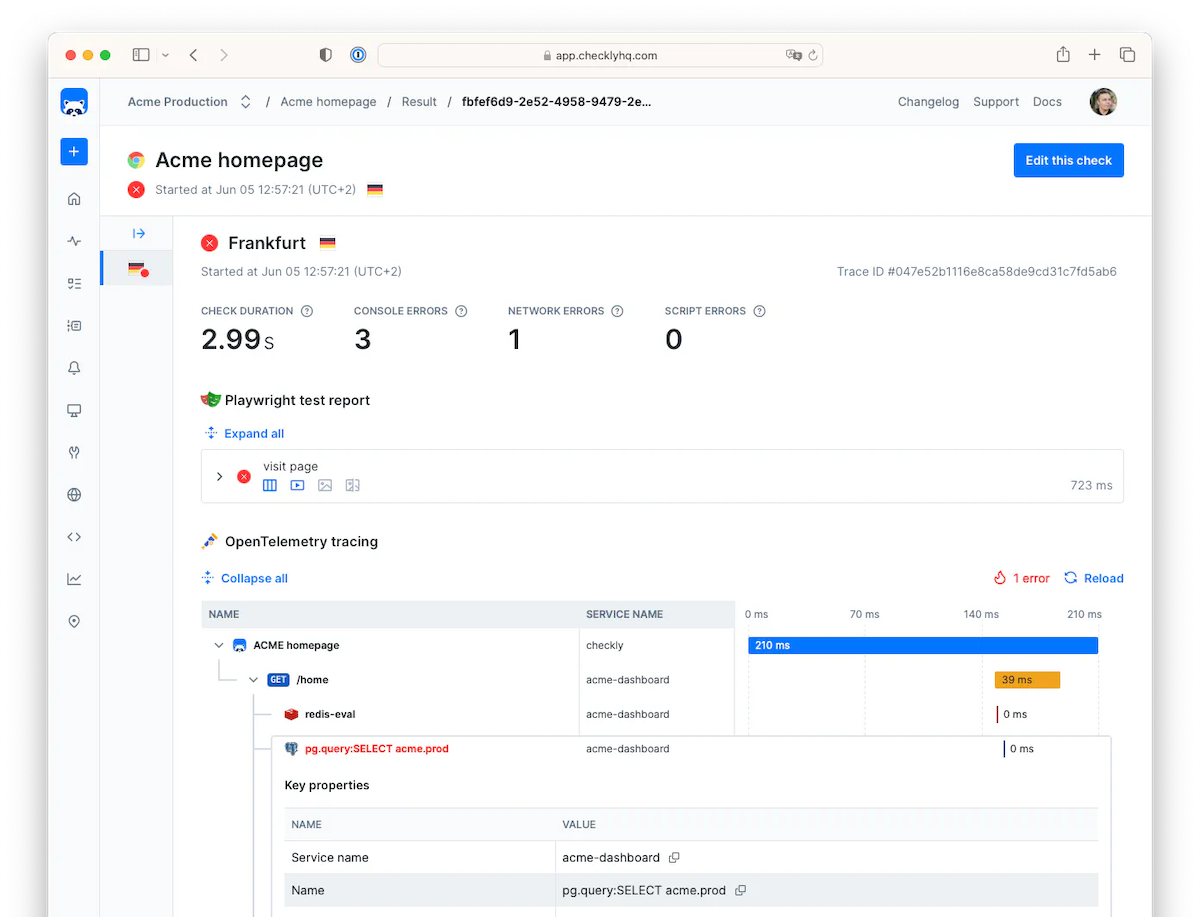

How Context Propagation Unlocks Efficient Monitoring: Checkly Traces

At Checkly, we had a problem. We wanted to let our users connect data on the backend performance of their application when handling requests sent by Checkly as part of synthetic user monitoring. For example, if a single postgres query was taking a long time and slowing down one type of user request, we wanted to see what request had taken so long. But we didn’t want to send large amounts of unecessary data, using up user’s bandwidth and resources. To continue the analogy, we only wanted to send the postgres query data for our specific test request, not all postgres query performance from everywhere. With OpenTelemetry context propagation, this proved feature was easy to implement, and performs well.

How it works: Context Propagation and Checkly Traces

- A user configures their Checkly test service to send requests with an additional header, marking this request as coming from Checkly

- The user adds a few lines of configuration to their OTel Collector, to send on relevant traces

- The service, instrumented with OpenTelemetry libraries, sees the header and passes it on between services

- When reporting a trace to the OpenTelemetry Collector, if the trace has the Checkly header, it’s sent on to Checkly

- Checkly’s reports on check results now have backend data, having sent only relevant traces to the Checkly server

Users of checkly data can see relevant backend performance data, but don’t send any timespans that aren’t necessary.

This is just one example of how context propagation is a key superpower for OpenTelemetry.

Conclusions: OpenTelemetry Context Propagation is Fundamental to Observability

Context propagation turns separate service logs into complete traces. It’s what makes modern observability possible. As systems grow more complex, this simple way of connecting services becomes essential for:

- Faster debugging

- Better performance tuning

- Understanding real user experiences

OpenTelemetry’s implementation gives you this power without requiring changes to how your services communicate. That’s why it’s becoming the standard way to observe distributed systems.