Table of contents

Update 13-03-2019: We moved our browser Checks to AWS Lambda! There will be a new write up!

At Checkly, we run our browser checks on AWS EC2 instances managed by Terraform. When shipping a new version, we don’t want to interrupt our service, so we need zero downtime deployments. Hashicorp has their own write up on zero downtime upgrades, but it only introduces the Terraform configuration without any context, workflow or other details that are needed to actually make this work in real life™.

This is the full lowdown on how we do it in production for ~1.5 million Chrome-based browser checks since launch.

The problem(s)

For those less initiated into “infra structure as code” and “immutable infrastructure” let’s look at the problem a bit closer. You will see that you have to build your app in a specific way and have some specific middleware (i.e. queues) in place to benefit from this approach. Skip this if you are a grizzled veteran.

You can chop this problem into a bunch of parts. Some are Terraform related, some are not, but they all need to be in place before you can pull this off without annoying your users.

For Checkly, the app in question can be defined as a “worker”. The workers processes incoming requests based on a queue of work. More on this in the architecture section. For now, let’s look at we want of our worker and of our worker deployment process:

Architecture problems

- Workers should be “killable” without impacting user experience.

- Workers of multiple versions should be able to coexist.

- Workers should be upgradable independently.

Deployment problems (solved by Terraform)

- New workers should start receiving production work as soon as they are ready.

- Old workers should be terminated only when new workers are up and receiving work.

- Botched releases should stop the roll out.

- It should work over multiple AWS regions.

Operations problems

- New workers should join any monitoring pool you have automatically.

- Botched releases should trigger alerts.

Some of these problems should be addressed during the roll out, where other should be addressed in your application architecture.

The architecture

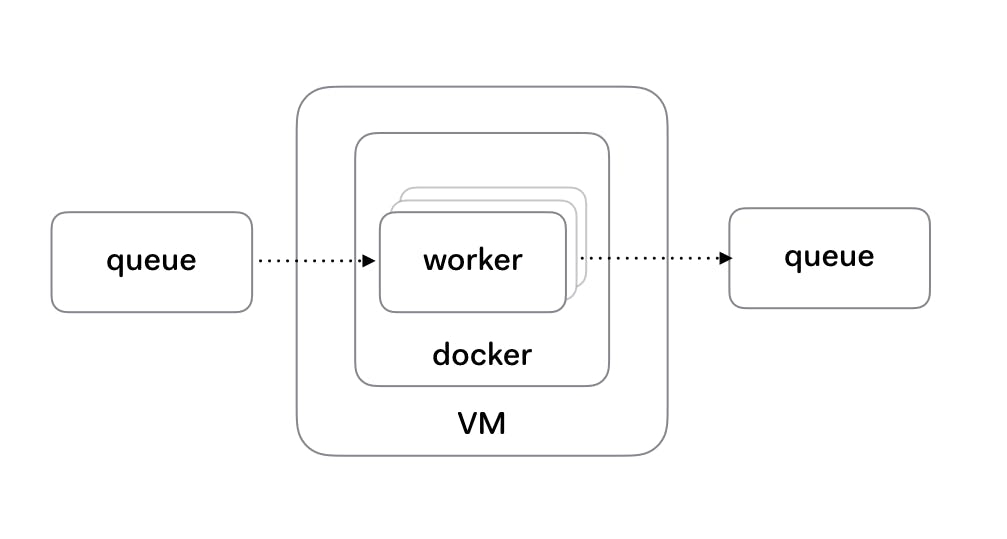

Some of the problems raised above can be tackled by following a typical fan-out / fan-in pattern or a master / worker pattern. This works especially well for the Checkly use-case because users do not interact directly with the workers.

In Checkly’s case, the architecture is as follows:

- A cron process pushes a check to an SQS queue. Each check is a JSON formatted message and represents one run for one check in a customer’s account.

- Workers subscribe to a queue. There are 5 active workers per EC2 instance. The worker is a Node.js process in a Docker container. Docker is not a necessity, but makes deploying easier as you’ll see in the next chapter. The worker uses the SQS consumer library. When a job finishes, it calls a

done()callback which deletes the message from the queue. - If work is not finished successfully, the

done()callback is never called or is called with an errordone(err). This triggers SQS specific behaviour where the message becomes visible again in the queue and other workers can pick it up. This is key, as we are now free to kill a worker without missing any work. This is an SQS function but comes with almost any queueing platform. - If work is finished successfully, the result is posted to another queue for processing and storage.

Applying this pattern solves our architecture related problems to the pattern’s inherent load balancing and decoupling attributes. Of course, this pattern also allows for pretty easy scaling. More messages === more workers.

Moreover, this also allows for some measure of auto scaling based on load characteristics like the amount of messages in a queue (and their relative age) or the 1m, 5m and 15m load average of the EC2 instances. The reason for this is that scaling up is easy, but scaling down without annoying users or impacting your service is a lot harder. Solving this issue for deployments also solves it for auto scaling. Two birds with one stone.

For anything even remotely stateful or interactive (i.e. API / Web servers with session state, data sources etc.) this pattern is pretty much a no go without something like request draining, sticky session based routing or a central session storage.

Terraform modules and config

As mentioned earlier, Terraform provides you with two primitives to do zero downtime deployments.

- the create_before_destroy flag in the lifecycle configuration block. Kinda speaks for itself. You can’t kill the existing servers before the new ones are up.

- the local-exec or remote-exec provisioner. This executes a command. When it return, Terraform continues its plan execution.

As you’ll find out, you need a bunch of other things to pull this off over multiple regions. Let’s look at anaws_instance configuration in a .tf file for Checkly.

// workers/module.tf

resource "aws_instance" "browser-check-worker" {

ami = "${data.aws_ami.default.id}" // AWS Linux AMI

instance_type = "${var.instance_type}"

count = "${var.count}"

tags {

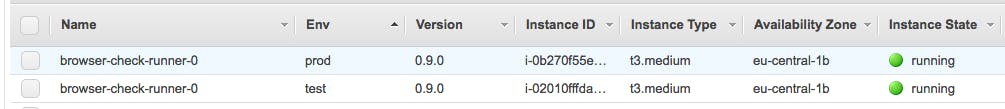

Name = "browser-check-worker-${count.index}"

Version = "0.9.0",

Env = "${var.env}" // prod or test

}

user_data = "${var.user_data}" // User data pulls & starst the app

key_name = "checkly"

lifecycle {

create_before_destroy = true

}

// Every 5 seconds, check if the launcher.js process is up.

provisioner "remote-exec" {

inline = [

"until ps -ef | grep [l]auncher.js > /dev/null; do sleep 5; done"

]

connection {

type = "ssh"

user = "ec2-user"

private_key = "${file("~/.ssh/checkly.pem")}"

}

}

}

Some take-aways from this file:

- We can tweak the AMI type, instance type and total instances per region.

- We explicitly tag each EC2 instance with the version of the code it is running.

- We pull in a

user-data.ymlfile that bootstrap the application. See more details below. - We provision a SSH key so we can connect to the instance.

The payoff is in using the remote-exec provisioner (that uses the SSH key). It checks every 5 seconds if the launcher.js process is running. Note we use the grep [l]auncher.js syntax to exclude the grep command itself from the process listing. Not doing this would instantly return this command and defeat the whole purpose.

Admittedly, this is fairly simplistic, but for our use case it does exactly what is needed. The existence of the launcher process means we have our code running and it is ready to read new messages from the SQS queue.

To fully grasp this, we need to look at a user-data file.

#cloud-config

packages:

- docker

write_files:

- path: /root/.profile

owner: root:root

permissions: '0644'

content: |

# ~/.profile: executed by Bourne-compatible login shells.

if [ "$BASH" ]; then

if [ -f ~/.bashrc ]; then

. ~/.bashrc

fi

fi

export NODE_ENV=production

export AWS_REGION=ap-south-1

export WORK_QUEUE=https://sqs.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/xxxx/checks

export RESULTS_QUEUE=https://sqs.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/xxxx/results

runcmd:

- service docker start

- [., /root/.profile]

- [docker, login, -u, checkly, -p, "pwd"]

- [docker, pull, "checkly/browser-checks-launcher:latest"]

- . /root/.profile && docker run -d -e NODE_ENV=$NODE_ENV ... checkly/browser-checks-launcher:latest

- We make the

dockerpackage a requirement. The AWS AMI we use has Docker preinstalled, but who knows… - We create a

.profilefile that contains the necessary environment variables our workers need to operate like the addresses of the two queues it communicates with, what region it is serving and in what environment it is working (production or test). - At boot, we start Docker and login to our private Docker repo. We pull the latest image of our worker and

docker runthe image, passing in all the environment variables.

Remember, none of this marks our new instance as “finished” from a Terraform perspective. The remote-exec command only returns after the docker container is fully running and has started the relevant node process.

The result looks as follows:

Note that this process is fairly generic. You can do the same thing for any Dockerized app or any Ruby, Python, Java, whatever app.

The AWS multi region Terraform configuration is very specific to how AWS manages naming, resources, access etc. per region. We also have Terraform configurations for Digital Ocean and they make it a lotsimpler to pull this off. We make use of the Terraform strategy described in this blog post.

The main thing to grasp is that for each AWS region, you create a module in your main.tf file, and reference the a template using the source attribute.

// main.tf

module "workers-us-east-1" {

source = "workers"

region = "us-east-1"

count = 1

user_data = "${file("user-data-us-east-1.yml")}"

env = "prod"

}

module "workers-us-west-1" {

source = "workers"

region = "us-west-1"

count = 3

user_data = "${file("user-data-us-west-1.yml")}"

env = "prod"

}

...

This leverages Terraform’s module hierarchy and allows you to fly in different variables for different regions. More importantly, it enables to deploy to multiple regions with one command.

But why create new instances anyway? The worker is published as a Docker container, can’t we just pull a new container, cycle the old one and be done with it? Yes, that works. We use it during development all the time. However, for production we want to be sure configuration hasn’t drifted due to manual intervention.

Deployment workflow

After setting all of this up, how do we release a new version of our worker? For Checkly, the steps are as follows:

First, we build a new Docker container. Tag it as latest and push it to our private repo. Nothing special here.

Secondly, we update the version in our module.tf file.

We then use the Terraform taint command to force a create/destroy cycle. Why? Because Terraform has no way of knowing that we want to pull a new container. Just bumping the version is not sufficient to trigger a replacement of the EC2 instance.

terraform taint -module=runners-us-west-1 aws_instance.browser-check-workerNotice that the -module targets an AWS region as per the module declarations in the main.tf file. From here, it is a straightforward terraform plan and/or terraform apply and ✨ behold the zero downtime magic. ✨

It doesn’t take a genius to see that this can be turned into a script that runs on a CI/CD platform pretty easily. It follows the general pattern of:

- build

- test

- package

- deploy

- monitor

Where each stage can break and return control to the operator. Your CI/CD platform will probably shoot you an email when that happens.

Monitoring

All of the above might fail. Reasons for failure might be as obtuse as AWS changing some API (breaking Terraform), your buggy code or just it being Friday afternoon. In general, failures fall into two camps:

- Deployment failures. These are easy and tricky at the same time. Firstly, they show up as you deploy. Your Terraform command returns an error. This can leave your multi region deployment in an undetermined state. I would recommend writing your code in such a way that your app can handle this. The alternative, a full roll back, tends to be even harder. Some manual work may be required.

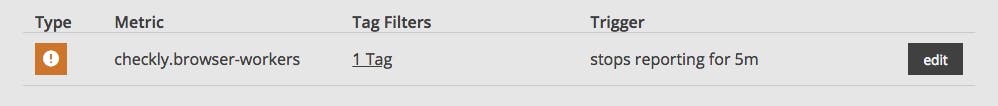

- Code failures. Your new version might deploy and even boot fine. It just might fail on some logic errors the moment it starts receiving traffic. For this you should either instrument your code with error tracking service like Sentry, Bugsnap or Rollbar. Next to that, I highly recommend having some sort of alert trigger “when nothing happens” for an x amount of time. For Checkly, we run appoptics.com(formerly Librato) and it alerts us when “nothing happens” for a workers in a specific region.

Note that this only works because our code explicitly calls the AppOptics API on each run, together with some basic details on what region the worker is running in, using the following code.

const axios = require('axios')

axios.defaults.baseURL = `https://${config.appOptics.apiToken}@api.appoptics.com/v1`

const namespace = 'checkly'

const trackRunCount = function () {

const payload = {

tags: {

region: process.env.AWS_REGION || 'local'

},

measurements: [

{

name: `${namespace}.browser-check-worker.count`,

value: 1

}

]

}

}

This is, again, specific to our situation as users don’t interact with the workers directly. In a typical client/web server scenario the amount of 500 errors, or the lack of 200 response codes could function as a similar trigger. In the end, you need to establish your app is processing user requests successfully, regardless of whether your deployment was successful.

Terraform also provides a ton of monitoring providers that you can hook into your deployment routine. If your particular monitoring solution is there, use it.

Conclusion

Doing zero downtime deployments with Terraform without causing service disruption is a bit more involved than just using the right Terraform commands and configuration. Takeaways are:

- Your architecture determines how easy / hard it is to do zero downtime deployments.

- Working infrastructure does not equal a working service.

- Everything can break, use monitoring at the infrastructure and service level.

- Humans will be needed when things break.

banner image: Sailing on a Blue Ocean” by Shotei Takahashi (1871-1945) - Japanese Open Art Database